Kerista Menu

|

Test Tube Lovers - Kerista's Ambiguous Utopia

From other issue seven, June 2005

http://www.othermag.org/content/kerista.php - (dead link 5/16)

By Annalee Newitz

"We want to make the world safe for rock 'n roll."

-- Eve, member of the Kerista family for 21 years, in a 1988 pamphlet

When a couple breaks up, there is no mistaking what has happened. Sure, there may be murky details. Who stopped wanting to have sex first? Who forgot to take out the garbage six nights in a row? Who started that horrible, final fight by making a face, or by refusing to answer a question posed repeatedly, or by not acknowledging the importance of arriving for dinner on time?

No matter what the circumstances, the narrative arc of the event - the loss of love and sorrowful separation -- is no mystery. We've heard breakup stories told a zillion times. We know the drill. Foolish rebound sex is had; ice cream is eaten; friends are sympathetic.

But if a romantic relationship deviates from the script, the stories dry up. There is no narrative framework to describe the terrible fights that ended the 21-year marriage of roughly two dozen people who called their family Kerista. It was not like Kramer vs. Kramer, not like a Hank Williams song, not like Sonny and Cher. It wasn't like when your parents got divorced, or when your best friends dumped each other after what seemed a lifetime of stability.

When an event is like nothing at all, we are tempted to forget about it. History leaves behind its aberrations. But I refuse to forget. I have my reasons.

When I walk past the houses where the Keristans lived during the 1970s and 80s - only blocks from my flat in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury district - I can imagine them going about their daily lives, making breakfast and writing and building their business and having parties and being in love with several people all at once. I can glance down Frederick Street and see them bustling around the small storefront that housed Abacus, their multi-million dollar Apple computer dealership. I can read the piles of idealistic newspapers and pamphlets they handed out at the space they called the Growth Co-op.

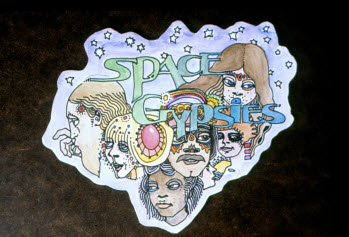

The people of Kerista invented the idea of polyfidelity - being romantically committed to more than one person simultaneously - and dared the world to look at them, to judge and imitate them. Members of the group toured the country, appeared on Phil Donahue and 20/20, were written up in countless academic studies and glossy magazines. They called it "life in the test tube," and believed that their experiments with reimagining the nuclear family could change the world.

Kerista and other groups like it gave a name to my experiences. Without them, there would be no record of what it's like to love more than one person at the same time, no map (however badly drawn) to lead me as I attempt to navigate multiple relationships in a culture which wants me to parcel out my desires and affections to only one person, as if there were a scarcity of feeling and it must be hoarded.

There is no social frame in which to place Kerista, but fourteen years after its dissolution it has become its own social frame. Cloaked in its context, poly people like me can begin to explain ourselves. We have our own epic love story - and, like all good romances, it serves as both a seduction and a warning.

Sleeping Schedule

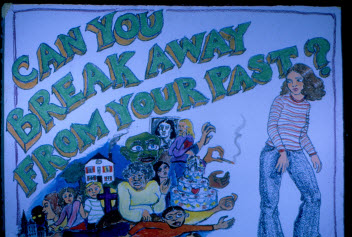

When Jud helped found San Francisco's Kerista commune in 1971, he attracted some of the first members using what co-founder and graphic designer Eve calls "a commune rap" that was very political. He promised an ethical, Utopian life ruled by principles; yet it would also break with establishment values and fit nicely with the wild hippie culture so popular at that time. Members of the family would be free to explore their artistic sides, to sing songs and draw cartoons rather than work a nine-to-five job.

Hoping to flee the constraining traditional families and straight life that they had grown up with, Eve and her best friend Eva Way signed up right away. They wanted an anti-family, an anti-marriage: a warm network of unrelated kin with whom they could be faithfully unfaithful. Over the years, they were joined by dozens of others who eventually occupied seven flats near the intersection of Frederick and Stanyan Streets, at the edge of Golden Gate Park.

Kerista was organized into subgroups with fanciful names like Purple Submarine and Sanity Mix -- members called them "best friend identity clusters." These clusters, which might contain anywhere from 4 to 15 people at a time, were marriages of polyfidelity: the people in them slept with each other and no one else. But the situation was flexible. If a person in Purple got sick of the scene there, he or she could court another cluster. Over the years, clusters formed and fell apart as membership in the commune changed or current members created new subgroups.

Luv, who joined Kerista in 1980, remembers that the early years of his marriage were idyllic. He was part of a small, four-person cluster called Jubilee and he loved the two women in his family tremendously. He continues to be close friends with the other man who was in the group (homosexual sex was not part of the Keristan agenda at the time). "Jubilee was magical," says Luv. "We were very gentle with each other, and that was the time when I got the most benefits out of Kerista's practices of sharing and communication. For a guy who wanted to learn about himself, it was wonderful."

One of Luv's jobs, when he first joined the commune, was to computerize the group's rather elaborate collective finances. Those were the early days of personal computers, and knowing how to use a spreadsheet program made Luv something of an expert. But he was also to computerize something else: the family's "balanced rotational sleeping schedule."

Until Luv arrived, the Keristans determined their nightly sleeping partners using something like a chore wheel. Nicknamed "the washing machine," this wheel listed every woman as a letter and every man as a number and was turned one notch each night. "We had the idea that you would be non-preferentially attached to each person," says Eve. And the most logical way to express this non-preferentiality was to use a system that guaranteed every person in a cluster slept with everyone else of the opposite sex in a cyclical order.

But the washing machine was getting unwieldy - there too many people to keep up with, and there was always the question of how to assign people to bedrooms. Electronic spreadsheets seemed like an ideal solution. It was this innovation that probably led to Kerista's reputation as a Utopian commune whose rap about free love was expanding to include a rap about the joy of computers.

You'd be surprised how often the scheduling demands of being poly drive us to technology. Let's say I have three partners and one of my partners also has another partner, who is married. How to plan our regular rendez-vous without having endless phone conversations with multiple people everyday? If I didn't have a sleeping schedule in my PDA, I'd go insane. Monogamous people accuse us of lacking in spontaneity for engineering our love lives. But as the Keristans used to say, what could be less spontaneous than sleeping with the same person every night? I know more than one group that plans their dates via a web-based calendar. I haven't gone that far yet. My partners and I have settled into a weekly routine, where certain nights are assigned to certain couples.

Unfortunately, the comforting routines of poly life do not breed perfect contentment any more than monogamous ones do. Fights are inevitable, and the Keristans tried to deal with strife as rationally as they dealt with sleeping arrangements. Jud introduced them to what he called "gestalt-o-rama," a group therapy process cobbled together out of pop psychology and method acting. When somebody got "gestalted," it was because they had failed to adhere to the commune's "social contract" - a fungible document whose dozens of principles each member agreed to uphold when they joined a Keristan cluster. Everyone remembers them as emotionally difficult encounters, often focused on one or two individuals who had broken a rule. Jud tended to lead the gestalts, peppering the offending family members with accusations and painful questions that Luv refers to simply as "brow-beating and manipulation."

The Kerista Town and Country Club

Although Kerista was run democratically, Jud was the eldest and most experienced member. He set the tone for the group - for better and for worse. He was always able to find untapped potential in his family members and nurture them into trying new things that gave them self-confidence and pride. But his temper was legendary.

Now in his eighties, this former Jewish kid from Brooklyn came of age as the Depression was ending and the war in Europe was spreading. While serving in the Air Force during World War II, Jud got into swinging. He says he loved sharing his wives (he was married four times), and when he returned to New York after the war with a sizable inheritance in his pocket he plunged into an upscale swingers scene full of socialites and showbiz types. During the late 1940s Jud got his first taste of the life he spent the rest of his days attempting to recreate in various forms. He joined a group that called itself the Kerista Town and Country Club, "full of movie stars, producers, and wealthy guys with beautiful apartments."

The group would get together on Friday nights in somebody's Upper East Side penthouse. At ten o'clock, Jud remembers, "We'd lock the doors, cook a wonderful meal, listen to some of the musicians play, and take off our clothes." The best part wasn't the sex. It was the companionship. Jud adored being surrounded by glamor and talent, beautiful "liberated women" and powerful men, people who could afford to spend all weekend talking philosophy. Perhaps this is why Jud used the name "Kerista" to describe every commune he created thereafter.

During the mid-50s, Jud became fascinated by the burgeoning Beatnik movement. He "dropped out," moved to Italy, and started taking a lot of drugs. But he was struggling with more than how to buck the establishment. "I was in the Philippines during the war, and I was responsible for a lot of killing. A lot," he says. "I tried to block it out, but I couldn't." He was plagued by terrifying flashbacks, nightmares, and insomnia. Then, in 1956, Jud had an experience that he sometimes calls a breakdown, and sometimes a revelation. While reading the Koran and smoking pot, he heard a chorus of male voices in his head telling him that he would be the leader of the next great religion. He still takes those voices very seriously, although he never heard from them again.

When Jud returned to the States, he created a short-lived commune in New York called Kerista. Like the version of Kerista which lasted for 21 years in San Francisco, the New York commune was based on free love and shared resources. The hipsters who populated it inspired countercultural writer Robert Anton Wilson to immortalize them in a 1965 article that spirals in a pot-induced haze around their dingy apartments in the Village. Wilson, like many observers of the Keristan community model, is fascinated by Jud's ever-expanding list of rules that every member of the group must follow. Jud may be a Beatnik, but his mind cannot unstick itself from the Air Force: the guy believes in order, and will brook no disobedience.

And yet his strict principles are hardly militaristic in flavor - they're full of exhortations to be "honest," "polite," "sensitive," "funky," and "non-sexist." Although adhering to Jud's principles was an often-painful process, Eve believes they're what held the Haight-Ashbury Keristans together long after other local communes fell apart.

We Come Bearing Apples

Kerista was also held together by work. During the 1970s and early 80s, the group ran a gardening and housecleaning business, as well as a small press that published pamphlets about the joys of communal life and polyfidelity. According to Eve, the pace of life in the commune during those early days was leisurely and fun. People had time to draw and make music - they created comic books and formed a band called Sex Kult. The family wasn't rich, but sharing everything made them feel that way. One room was devoted to women's clothing: big dressers and a bulging closet were full of every possible outfit and costume imaginable. Everyone had access to a groovy wardrobe that none of them could have afforded on her own.

Money was handled as collectively as possible. Each Keristan had his or her own bank account, but in general expenses were paid out of a communal checking account for food, housing, and incidentals. Most of the Keristans worked in the commune's own businesses; the few "hunter-gatherers" like Luv who had outside jobs happily gave large chunks of their salaries to the group. "I felt great that the majority of my check went to the commune fund," says Luv. "I thought that everybody was pulling their own weight, working on publications and the cleaning business. I thought it all evened out." When somebody new joined Kerista, the group took careful inventory of all the money and other items he or she brought in - people always left with everything they had come with. People who joined with no money were given $600.

Unlike many communes of the era, including the kibbutzes that Jud admired, Kerista always embraced capitalism. "We were trading just like everybody else," says Eva Way. "Instead of doing it to support a family, we were doing it to support a community and tribe. Nobody saw our business as subversive."

With the money they made, the Keristans were able to fund their creative projects, throw parties, and go on frequent group vacations. There were always cool people around their flats to do things with - nobody ever lacked a big posse of friends who were ready to go dancing, catch a movie, or just sit around and talk about the meaning of life over dinner. It was like the best parts of family life had been rolled up together with the best parts of romance and friendship. Everybody shared the burdens of creating a decent living for themselves, and they did it out of a sense of fun and adventure rather than duty.

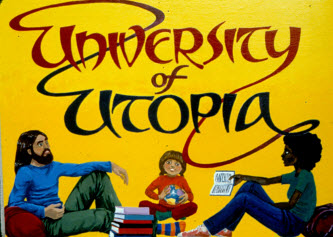

Kerista's modest entrepreneurial ventures went into high gear in the mid-1980s. Wild with excitement, Jud told the family that he had a new plan for their future - the commune would remake itself as a kind of Utopian marketing firm. They would earn as much money as they could and put it into exporting their way of life to people all over the world. With extra cash and a more corporate spirit, they could change society even more quickly than they had planned.

How would they do it? Apple computers.

At the time Jud announced the group's new direction, the family was already enchanted with Apples. Eve used them for graphic design and layout for their newsletters. Luv was using them for his financial spreadsheets. Other people just used them for games.

Leander Kahney, author of The Cult of Mac, says it make sense that the group gravitated to Apples, which were marketed as the the countercultural alternative to products from uptight IBM. Apple's power as a company was expanding just as the Keristans decided to go into the computer business. "They rode [Apple's] popularity into the stratosophere," says Kahney. "They became the biggest computer business in Northern California."

Several Keristans began doing computer-related work out of a storefront on Frederick Street that they called "Utopian Technology." A Keristan named Larry wrote a contact management system for them, which they sold bundled together with Apples in order to become what was called a value-added reseller. Eventually, Eva Way brainstormed a plan to get Apple's then-CEO John Scully to turn them into an Apple dealership. She walked straight up to him after he'd given a keynote at a conference and said, "Hey, if you want to promote women in your business, why don't you help us become the first women-owned dealership in the region?" Within weeks, they'd been granted dealership status, and soon had service contracts with several extremely large corporate customers.

What turned their small business into a 3-million-dollar-a-year operation was the Keristans' flair for educating people. They never set up computers for a customer without tutoring each employee for at least three hours in how to use them. "We'd send our people in to deliver computers, and they were all cute hippies," Luv recalls. "Word spread like wildfire about this company called Abacus - it was great viral marketing." Formerly a gardening and housecleaning company run by cultural rebels, Abacus became one of the top 20 Apple dealerships in the nation.

Their high tech business, so rare among hippie communes, also revealed something even more unusual about Kerista: women were given as much authority as men. Although men helped run Abacus, it was owned and steered by women. And everyone knew that Eva Way was a big part of their financial success. This respect for women spilled over into other parts of their daily lives. Men were expected to cook for themselves, and to participate in childcare as much as the women were. (The Keristans had two children, and occasionally other kids visited.) When the family decided that two children were enough, the men made the unusual decision to take responsibility for birth control and got vasectomies. After a certain point, men couldn't join Kerista unless they had had a vasectomy.

Eva Way says she and many of the other women took 1980s rock icon Joan Jett as their female role model - Jett was tough, sexy and took shit from nobody. "She represented freedom and expressing yourself," says Eva Way, who ran the Haight-Ashbury Joan Jett fan club. But Jett's appeal wasn't just as a kind of accidental feminist. She also represented a new, more exciting kind of popular culture. "By that time, we had blue hair and stuff," Eva Way laughs. "We were sick of hippie bullshit and understood punk. You can't stay stuck in the 70s forever."

Cult of the Family

As the family's fortunes followed those of many people who got rich in the 1980s, cracks began to appear in their edifice of equality and democracy. Some members of the family worked much longer hours than others - "It bordered on workaholism," says Luv, and it undermined their ability to bond with each other emotionally. Hierarchical relationships formed among the members, leading to power imbalances and cliquish schemes. And on top of all that, the commune was run in a way that made it harder and harder for its members to express their feelings and reservations honestly.

It also bordered on being a cult. Many Keristans say in retrospect that they should have noticed the telltale signs: They were forced to agree to Jud's principles without question, and nonconforming members were gestalted into submission. Although it was supposed to be a vehicle for self-discovery, the gestalt-o-rama evolved into a way for Jud to abuse people who disobeyed or displeased him. Many family members fled the group after three or four years because "being gestalted" hurt so much and seemed unfair. Psychologically, the group was ruled by Jud. Sometimes, his praise lifted them so high that they could succeed at anything; but sometimes he gestalted them to tears. He was their patriarch, their inspiration, and perhaps, sometimes, their cult leader.

And yet to friends of the group, it seemed much more like a close-knit community than a Scientology setup. "It was totally uncultish," says Daniel Kottke, a former Apple employee who attended many Kerista events and parties, and dated a Keristan after the group broke up. "It's true that everybody took those new, three-letter names, but aside from that they just threw parties and had fun. There was no recruiting." Eva Way says the cultiness of the group wasn't glaring. "There was nothing totally weird, just little weirds, like the way Jud would be rude but you couldn't call him on it," she says. "He would always turn it around and say you were the one at fault."

What is a cult but a dysfunctional family writ large? I think of my own father, a patriarch as principled as Jud tried to be, screaming at me for hours about how I would never amount to anything because I refused to follow his elaborate rules and adopt his opinions. I was a liar, stupid and lazy - except for those times when I was perfect, the best daughter in the world who could do anything. I've heard those fights and witnessed bipolar swings between irrational wrath and adoration in other families too. Even in the most loving, stable families, there are moments when abusive hierarchies develop: overworked fathers berate stay-at-home mothers (and vice-versa); parents unfairly punish their children; an older sister locks her younger brother inside the laundry hamper.

Even more common, although less widely acknowledged, is the fact that families smother our true feelings. It was in a family where I first discovered that coercion can substitute for intimacy, and that having an emotional outburst is not the same thing as sharing feelings.

These lessons also seem to be what the Keristans ultimately learned about the family they built together. Because the preferred method for resolving problems was the group gestalt-o-rama, there was little room for individuals to work out problems with each other in private. Instead, there were just rules and their public enforcement. At their worst, the gestalts became a way to force clusters to accept new partners even when several members weren't sure they wanted to. "There were times when I consented to new women that I didn't really connect with sexually," admits Luv. "There was peer pressure, and a lot of people found themselves in awkward situations as a result."

In hindsight, it's easy to use bad times to color everything that's gone before. But the Keristans, like many families, supported each other as often as they tore each other down. They even invented a word, "compersion," which means "taking pleasure in another person's happiness." It is the opposite of jealousy, the sort of idea which could only take root in a community centered on sharing and group life, rather than possessiveness and individualism.

Mutineers

Jud feels the commune began to drift away from him after he became impotent in his sixties. "I was the old man rather than the lover," he recalls sadly. He blames the breakup of Kerista on a group of people he calls the mutineers. They went crazy, he says, and took his money and projects away from him. But the story is obviously more complicated than that.

It was 1991, and the big chain stores like CompUSA were driving independent computer dealerships like Abacus out of business. The Soviet Union was collapsing and the papers were full of headlines about how an entire confederation of states was rebelling against a socialist system the Keristans couldn't help but compare to their own. Everybody in the group hit their mid-life crises around the same time. Eva Way says they all got "sick of communism," but Luv believes they had become such workaholics that everybody just burned out.

Eve thinks the Keristans tried to mandate desires in a way that simply went against human nature. Especially when it comes to whom we lust after and love, democracy may not be the best policy. "There were too many compromises," sighs Eve. "You can't get a large group to agree on most things, and we wanted people to agree on everything." New ideas were shut down, and the old platitudes were wearing thin. Meanwhile, Jud had become increasingly depressed and combative. Longstanding members of the group were thinking about leaving to escape his verbal assaults.

Led by Eve and several other members of the Purple Submarine cluster, the Keristans eventually agreed that the next time Jud called gestalt they would fight back. Eventually the day came. There was a gestalt over something fairly routine for the group -- a conflict had developed over whether they should allow a couple of new men into the family. Jud started on a tirade and tried to get members of the group to go along with him. But nobody would. He pushed harder. The group refused to toe his line. And then, for the first time, they began to gestalt the gestalter. It wasn't long before Jud left in a huff. Days later, the Keristans voted to dissolve their family.

Eve and five other Keristans moved to Hawaii, bought some land together, and tried to continue their polyfidelous family. But they quickly paired off into monogamous couples - two of the couples are still married today. Very few of the Keristans are poly these days. "I wanted the intimacy of monogamy," says Eva Way. "I didn't want to be equally special to ten other people - I wanted to be number one!" Most of the other former Keristans seem to share her sentiments. Jud, however, remains staunchly polyfidelous. He's still close to a few of the former Keristans, including his daughter.

Today, many of the Keristans have jobs related to what they did in Abacus. Several are in business for themselves, doing computer-aided graphic design, financial planning, and nonprofit work. A few of them, like Luv, live in group houses.

But for the most part, the Keristans have left communal ownership behind. They remember their social experiment fondly, but can't imagine doing it anymore. Even the Hawaiian contingent eventually divided up their land into separate houses and plots. "All we own together now is a tractor," Eve says.

I think about that tractor a lot.

|